This is a guest post by Kara Gebhart Uhl and Christopher Schwarz written for Lost Art Press.

One night I looked at my woodworking friends sitting around the table and asked: “Can you explain to me in simple terms how plywood exists? Why does it not tear itself apart when you glue a 48″-wide layer to a 96″-long layer and they are cross-grain?”

Several of them opened their mouths to speak. Then they gave it some thought. Then they closed their mouths.

After a few minutes of silence, they offered some ideas. But none had an answer we could all agree on.

Why does plywood get to disobey most of the rules of wood movement?

I asked Kara Gebhart Uhl, our researcher, to find out. This is her report.

— Christopher Schwarz

Have you ever looked at a plywood panel and wondered how it exists? In particular, why does wood movement not tear apart the glue bonds between the plies?

We have.

In part one of this two-part series, we’ll discuss how plywood came to be, how it’s made and why it works. In part two of this series, we’ll discuss the different types of wood and glues used to make plywood, as well as its sustainability.

Whether you love or hate plywood (or just tolerate it), you’ll understand how it works. Let’s get started.

A Short History of Plywood

“Plywood is a material that is widely known yet, remarkably, little understood,” writes Christopher Wilk in his book, “Plywood: A Material Story,” published to accompany “Plywood: Material of the Modern World,” a 2017 exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum. “Seen in the public imagination as both a mundane and ubiquitous material of building sites and domestic do-it-yourself (DIY) projects, and also as a material of high-style architecture and design, plywood has a long history that is largely unknown and has been little researched.”1

According to Wilk, while the word “plywood” wasn’t commonly used until the 1920s, the idea of gluing together perpendicular layers of veneer has been around for centuries. One of the earliest examples of this type of construction technique was found in a coffin made around 2649-2575 BCE in Egypt.1

Fast forward to the late 1850s, when John Henry Belter patented a moulding furniture technique in New York. You can see an example of a moulded plywood back in this insanely ornate chair.2

In 1858, Bruno Harras founded the first plywood factory in Germany.3

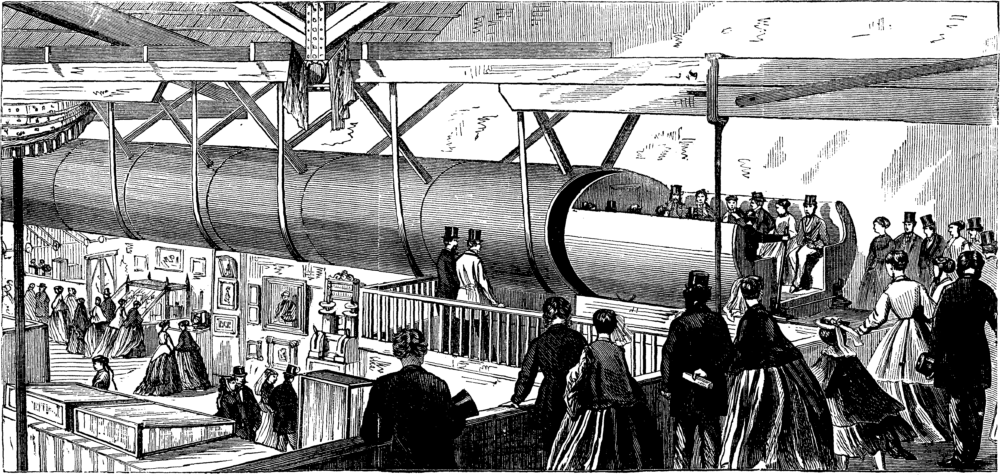

The Victoria and Albert Museum shares a small sampling of the fascinating evolution of plywood use, including a 107-foot-long elevated railway on exhibit at the American Institute Fair in 1867, as well as a canoe, a car, a boat, chairs, a leg splint and a factory-produced house.2

“Modern plywood dates back to the early 20th century – actually in Oregon,” says Jeffrey Morrell, Ph.D., director of the Forestry Centre of Excellence at the University of South Australia and executive board member of the International Society of Wood Science and Technology.

In 1905, Portland Manufacturing Company produced “3-ply veneer work” for a World’s Fair, drawing interest from different manufacturers, particularly those who made door panels. By 1929, the Pacific Northwest was home to 17 plywood mills. The APA – the Engineered Wood Association – was founded in 1993 (originally named the Douglas Fir Plywood Association).4

Wilk devotes an entire chapter to “The Veneer Problem (1850s–1930s)”: “The ‘anti-veneer’ sentiment ran deep in nineteenth-century popular culture and it is not possible to understand the lowly status of veneer and plywood in the eyes of the public without a clear explanation of its origins.”1

As the wood industry worked hard to change society’s views of plywood, the aircraft industry began to take note of its durability and strength.1 The development of strong, waterproof adhesives gave rise to more plywood applications, particularly by architects; manufacturers of automobiles, boats and airplanes; and the building industry.1

In 1945, Charles and Ray Eames designed the DCM chair.5

“It is not hyperbole to claim that the DCM became the most influential and imitated chair of the mid-twentieth century and that it contributed immeasurably to the domestication of plywood: not only did Eames-influenced furniture appear in high-style or design-conscience interiors, but it was also instrumental in plywood becoming a staple of mass-market commercial and institutional furniture,” writes Wilk.1

By 1982, there were 175 plywood plants in the U.S., “with a combined production capacity of nearly 23.1 billion square feet per year, 60 percent greater than in 1965,” according to FPL.6

By 2023, the global trade of plywood reached $15.5 billion, with the U.S. as its top importer.7

Plywood’s Place in Wood-based Composite Panels

The Centennial Edition of “Wood Handbook: Wood as an Engineering Material,” published by FPL, is an excellent resource for anything you wish to know about wood-based composite materials. This type of material is typically made by bonding wood veneer, flakes, fiber, chips, or sawdust with a strong thermosetting adhesive, meaning it’s pressed at high temperatures to cure, or permanently set, the glue.3,8

FPL organizes wood-based composite materials into three categories.

Panel products include:

- Plywood: Made from plies (thin slices of wood) oriented perpendicular to each other and bonded with adhesive that’s pressed under high temperatures

- Oriented strandboard (OSB): Made from thin strands or flakes of wood, mixed with wax and adhesive, and pressed under high temperatures

- Particleboard: Made from sawdust, wood chips or planer shavings, mixed with wax and adhesive, and pressed under high temperatures

- Fiberboard: Including hardboard, medium-density fiberboard (MDF) and cellulosic fiberboard, made from processed wood fibers that are the same size, mixed with wax and adhesive, and pressed under high temperatures8

Structural timber products include:

- Glue-laminated timber (glulam): Made from lams (wood planks or strips that are glued parallel to each other) and bonded with adhesive that’s pressed under high temperatures

- Structural composite lumber (SCL): Including laminated veneer lumber (LVL), laminated strand lumber (LSL) and parallel strand lumber (PSL), made from wood veneers, strands or flakes and bonded with adhesive that’s pressed under high temperatures and formed into billets (blocks of material), which are sawn to specific sizes8

Wood-nonwood composites (WPC) are made of wood materials, such as fibers or particles, and non-wood materials, such as plastic or cement.8

How Plywood is Made

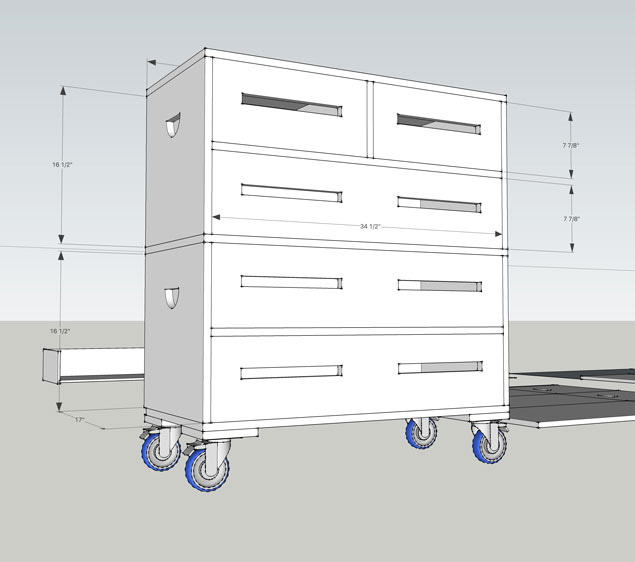

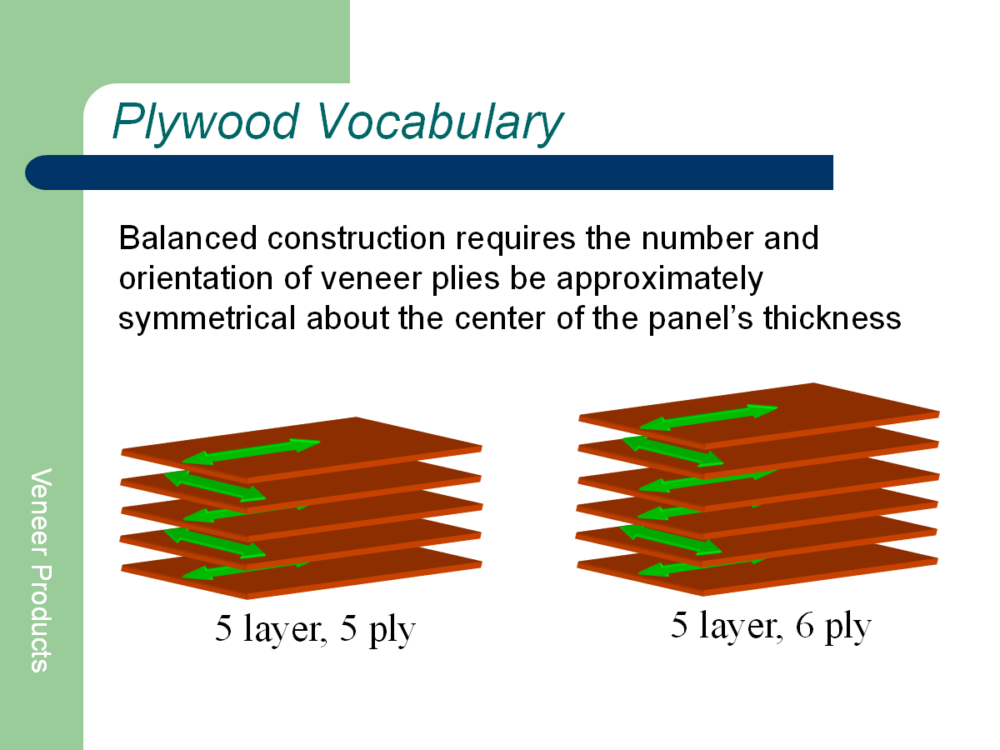

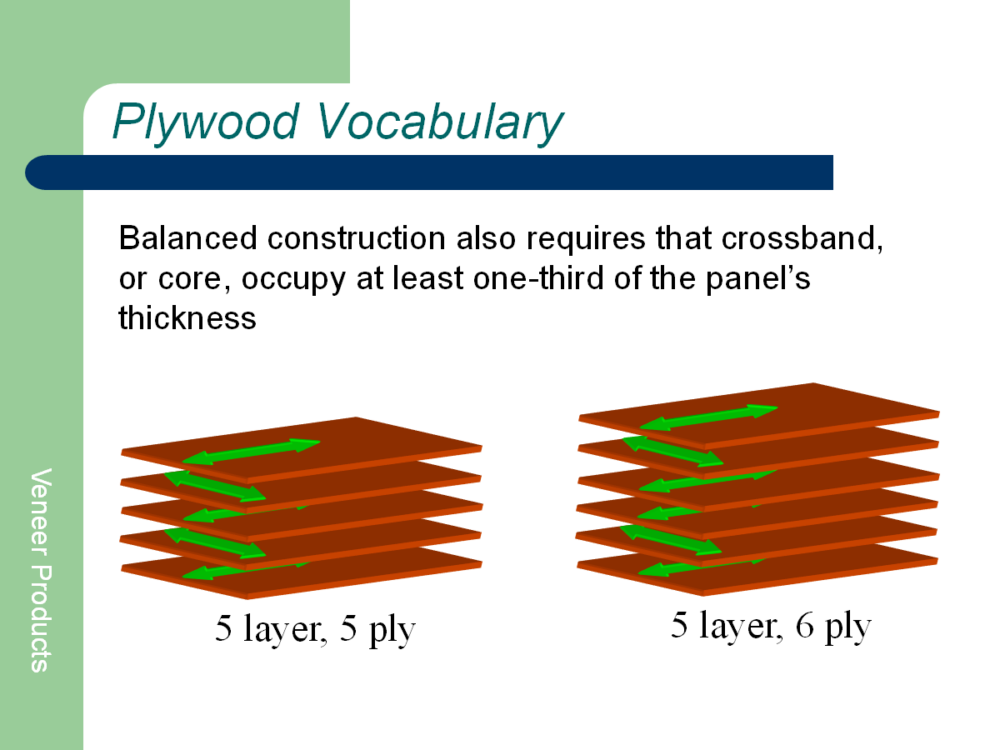

Plywood is made up of layers of plies. Sometimes layers are single ply, sometimes they are two-ply (or many-more ply). When plies are laminated together, the grain direction on the plies can be parallel. The number of plies in a plywood panel can be even or odd.8

Layers are another matter. The grain direction on the layers is always perpendicular. And the number of layers in a plywood panel is always odd.9

You may see plywood described as “four-ply, three layer.” This describes the number of plies and the layers.8

Morrell shared with us some slides from one of his lectures, demonstrating balanced plywood construction and providing a good visual of the differences between plies and layers.

“Panels are balanced so that stresses from dimensional changes in one direction are offset by those in the other,” Morrell says.

There are two broad categories, or classes, of plywood: structural grade and non-structural grade. FPL distinguishes structural plywood as construction and industrial plywood, and non-structural (or appearance grade) plywood as hardwood and decorative plywood. Non-structural plywood is meant for indoor use – things like furniture and cabinets.8

The fact that non-structural plywood is often referred to as “hardwood plywood” can be confusing, says Scott Leavengood, professor and director of the Oregon Wood Innovation Center in the department of Wood Science & Engineering Outreach and Engagement at Oregon State University. That’s because sometimes the core material in “hardwood plywood” is particleboard, and the face layers are thin layers of softwood such as vertical-grain Douglas fir.

In the U.S., different agencies grade plywood, providing third-party certifications, each with its own trademarked grading names and systems. Plywood grades reflect the quality and appearance of a plywood panel. Plywood with higher grades is often used for furniture and cabinetry. Plywood with lower grades is often used in situations where strength is more important than appearance (for example, subflooring).8

Wood Movement’s Effect on Plywood Through the Lens of Glue

The adhesives used in plywood, Leavengood says, must be very strong to resist any shrink/swell forces. Phenol formaldehyde (PF) is the most commonly used adhesive for structural plywood. Decorative panels tend to offer greater flexibility in adhesives, but urea formaldehyde (UF) is the most commonly used. (We’ll talk more about the different types of adhesives in plywood in part two of this series.)

When wood is exposed to moisture (through things like rain, wet shoes or humidity), it expands. When wood dries, it shrinks. Even in plywood, Morrell says, “Eventually, if you cycle moisture enough, you will get wood failure. But you’ll always get wood failure, not resin failure, because that bond is stronger than the wood.”

In fact, this is one way plywood is quality tested, Morrell says. If you pull a panel apart and get more resin (glue) failure than wood failure, the panel fails the test.

Kyle Freres is vice president of Freres Engineered Wood, a family-owned company founded in 1922. In the 1950s, they began producing veneer, added plywood in the 1990s and most recently, mass ply products. Freres says many of their quality assurance tests are designed to demonstrate how wood in plywood fails before the glue.

“Essentially, resins are polymers, but when you use them, they’re monomers,” Morrell says. Most types of plywood use thermosetting adhesives. “You add heat to get the reaction to crosslink the monomers to make a polymer, which means they’re permanently set. So in essence, it becomes like plastic.”

(Ed: OK, this is an important point that I’ve never heard. So take note of it.)

From “Wood Handbook”: “The properties of plywood depend on the quality of the veneer plies, the order of layers, the adhesive used, and the degree to which bonding conditions are controlled during production. The durability of the adhesive-to-wood bond depends largely on the adhesive used but also on control of bonding conditions and on veneer quality. The grade of the panel depends upon the quality of the veneers used, particularly of the face and back.”8

Perhaps you’ve heard of WFP, or wood failure percentage. This is a measure of bond quality.

“Bonds are pulled apart in tension parallel to the bond line, and then the WFP is assessed – the higher the number, the better,” Leavengood says. “In short, manufacturers want to see the wood fail rather than the adhesive. Cross lamination helps to restrain the shrink/swell forces given the very high strength of wood along the grain, and again, the adhesive maintains the rigidity.”

Wood Movement’s Effect on Plywood Through the Lens of Cross Lamination

Veneer-based plywood was invented, in part, to balance the natural movement of wood, Leavengood says.

Wood wants to move, Freres says, particularly when it gets wet or dries out, but it moves predictably. Traditional plywood panels alternate the grain direction perpendicular to each other to provide strength along the length and width of each sheet.

“This is why plywood can be much wider than a typical board and remain strong in both directions,” Freres says. “The ‘thinness’ of each veneer ply is also a benefit because you get additional strength by laminating multiple layers together, and this has the added benefit of distributing any defects in the ply throughout the panel. When blocks are peeled, defects that might be a significant problem in a board are randomized through the various plies of a panel and become less significant.”

And while each ply, or slice of veneer, may look solid, Morrell says there are actually little checks inside each piece.

“And the way they make panels, when you peel on a rotary lathe, it’s kind of like paper towels,” Morrell says. “There is a direction to the veneers, and there tend to be more checks on the outside of the roll than the inside. And so there are already lots of channels in there to relieve stress in the veneers.”

(Editor’s note: That is another important point. Basically, plywood can exist because the glue they use is incredibly strong and the wood has been weakened just a touch. This makes sense.)

Plywood is prized, in part, because of its strength.

From “Wood Handbook”: “Plywood panels have significant bending strength both along the panel and across the panel, and the differences in strength and stiffness along the panel length versus across the panel are much smaller than those differences in solid wood. Plywood also has excellent dimensional stability along its length and across its width.” Also: “The alternating grain direction of its layers makes plywood resistant to splitting, allowing fasteners to be placed very near the edges of a panel.”8

However, decorative plywood panels can be a different matter, Leavengood says.

“I’ve done a bit of research on checking (i.e., splitting along the grain) in the face veneers of decorative panels where the face veneers are often less than 1 mm thick,” Leavengood says. “These thin veneers often do not have the tensile strength to resist the shrinkage stresses when going from locations of high humidity to low humidity. This is a pretty costly problem for manufacturers in that the failures often occur once installed – such as in your kitchen cabinets. Costs of the panels themselves are trivial compared to the cost of replacement.”

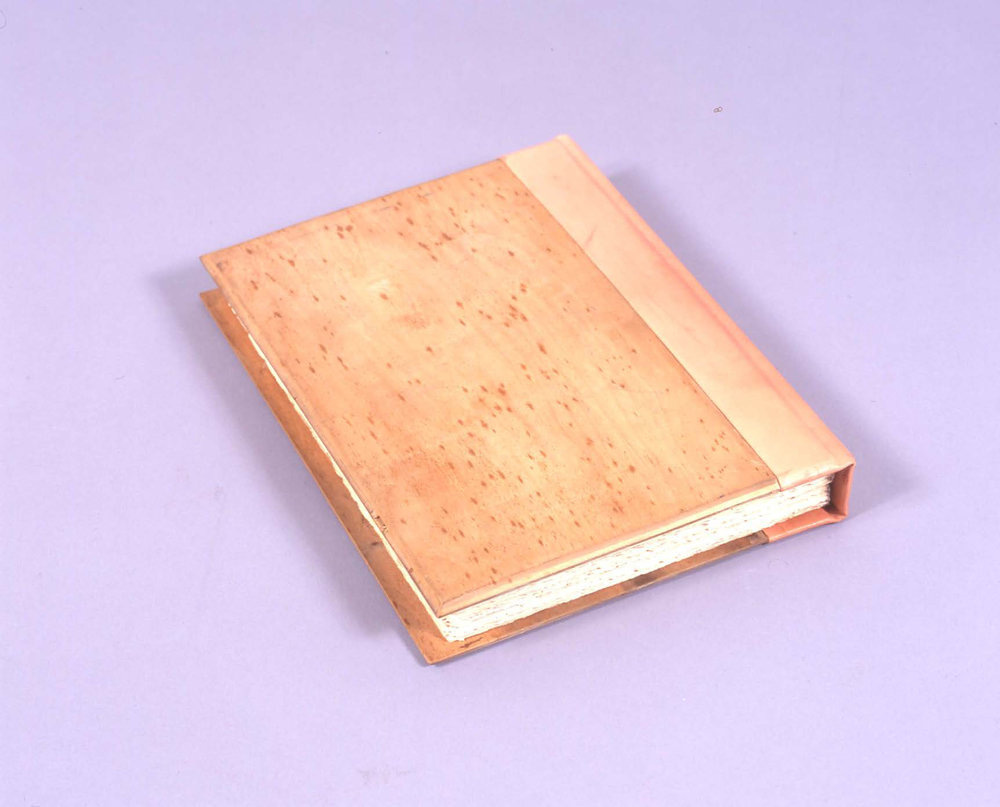

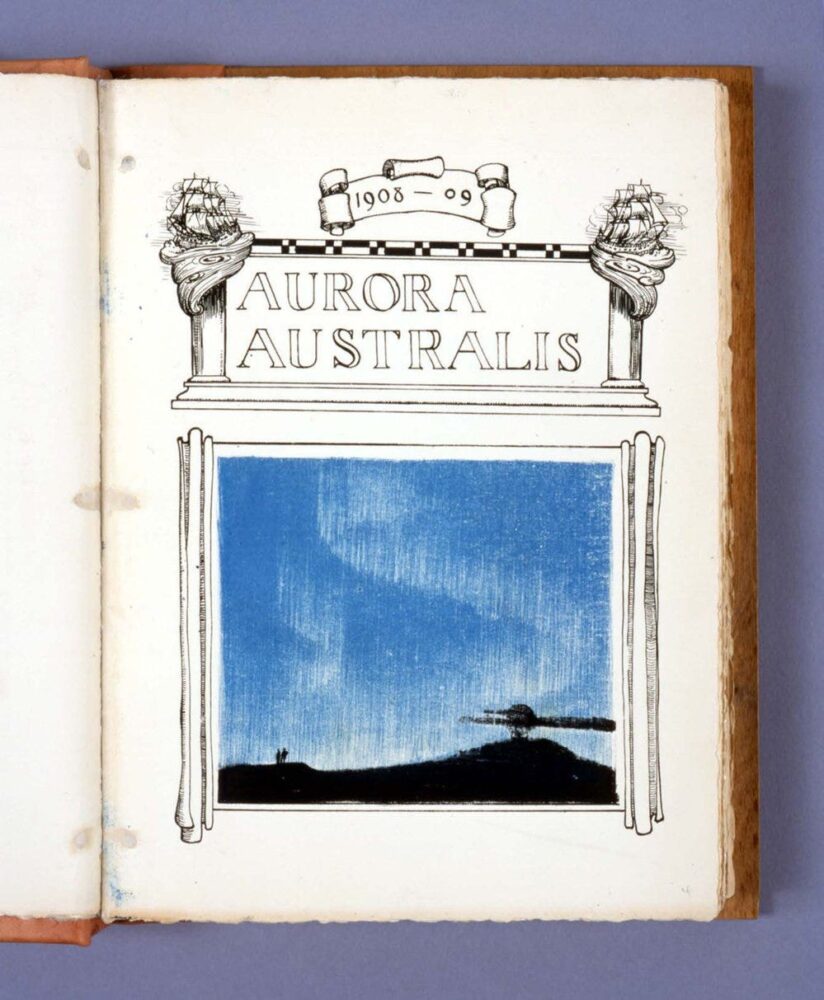

Sometimes, plywood persists in even the most unlikely situations. Take, for example, Ernest Shackleton’s 1907 to 1909 Nimrod Expedition to Antarctica, which required 2,500 packing cases.

“Plywood was chosen for its lightness and strength,” according to the Victoria and Albert Museum. “The cases were able to withstand extreme Antarctic conditions, including being buried beneath ice during blizzards. They were reused by the crew to make furniture for their living quarters and as covers and binding for ‘Aurora Australis’ – the first book to be written, illustrated, printed, published and bound in the Antarctic. Astonishingly, Shackleton and his crew took a printing press on their expedition to ‘guard [them] from the danger of lack of occupation during the polar night’.”2

In 1997, one of these packing cases sold at Christie’s for $20,000.9 (Ed: So plywood stuff isn’t always cheap.)

Plywood, Morrell says, “has a number of advantages. You can make bigger panels out of smaller logs. Plywood also allows you to create a product with good strength properties in multiple directions and optimizes wood recovery. Finally, you can sort veneers based upon their strength, so that you place the strongest veneers where they are most needed.”

Stay tuned for part two, where we’ll take a closer look at the types of wood and adhesives used to make plywood, as well as its sustainability.

For more content like this, visit Lost Art Press.

Sources:

- Wilk, Christopher. “Plywood: A Material Story.” Thames & Hudson. 2017.

- “A short history of plywood in ten-ish objects.” Victoria and Albert Museum. Accessed October 30, 2025. https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/a-history-of-plywood-in-ten-objects

- Wagenführ, A., Buchelt, B., Kairi, M., Weber, A. “Veneers and Veneer-Based Materials.” In: Niemz, P., Teischinger, A., Sandberg, D. (eds) “Springer Handbook of Wood Science and Technology.” Springer Handbooks. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81315-4_26

- “History of APA, Plywood, and Engineered Wood.” APA – the Engineered Wood Association. Accessed October 30, 2025. https://www.apawood.org/apas-history

- “DCM.” Eames Office. Accessed October 30, 2025. https://www.eamesoffice.com/the-work/dcm/

- McKeever DB., Meyer WG. “The Softwood Plywood Industry in the United States, 1965-82.” Res. Bull. FPL 13. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory. 1983. https://www.fpl.fs.usda.gov/documnts/fplrb/fplrb13.pdf

- “Plywood.” Observatory of Economic Complexity. Accessed October 30, 2025. https://oec.world/en/profile/hs/plywood

- Forest Products Laboratory. “Wood handbook—Wood as an engineering material.” General Technical Report FPL-GTR-190. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory. 2010. https://www.fpl.fs.usda.gov/documnts/fplgtr/fpl_gtr190.pdf

- Worthington C. “Mining the Relics of Journeys Past.” The New York Times. Nov 22, 1998.

https://www.nytimes.com/1998/11/22/arts/art-architecture-mining-the-relics-of-journeys-past.html

Subscribe

We’ll send you a notification when a new story has been posted. It’s the easiest way to stay in the know.